Research interests

Epoch of Reionisation and the Ionosphere

These days, I’m working as a low-frequency radio astronomer with the MWA, with the ultimate goal of detecting the Epoch of Reionisation. To aid detection of the EoR, much of my recent research has involved characterisation of ionospheric activity.

More to come…

Star formation

My exposure within star formation research includes:

- dense gas tracers, such as $\text{CS}$ $(1-0)$ and $\text{NH}_3$ $(1,1)$

- methanol masers, particularly the poorly understood class I variety

- instrumentation and software development, for observational planning and data reduction pipelines

Most of this interest is generated by my PhD project, MALT-45. More on MALT-45 can be found below.

As I’m an observational astronomer, I am interested working with other instruments and regimes (sub-millimetre, near-infrared, etc.) ALMA is particularly exciting within the star formation community, providing unprecedented resolution and sensitivity.

Currently, I have around 350 hours of experience on the Australia Telescope Compact Array, particularly with its relatively new 64M-32k correlator mode.

Perhaps before touching on the question “what is star formation?” we should ask, what are stars?

Stars

Stars, to me, are freaks of nature. Looking into space, we see vast emptiness; it's mostly empty (hence space). Yet it's littered with these bright spots everywhere we look. Indeed, one may think of stars as the grains of sand that build the universe, but indulge me...Stars represent regions of space where enough "stuff" is contained in the same place; so much so, that fusion is allowed to take place, and naturally radiates a huge amount of energy. A star would gladly colllapse upon itself further if it could, but its structure is provided by the intense fusion in the core. The fusion effectively pushes the mass "falling" into the core outwards. This "collapsing" and "pushing" results in a hydrostatic equilibrium, meaning that the size of the star depends on the strength of each force constantly fighting (gravity vs. outward pressure). If there's more mass, there's more gravity, but consequentally there's also more fusion. However, stars with more mass are bigger than those with less.

If there was less matter in these stars, these "failed stars" would barely shine. Throw in some more material, and you get much more extreme consequences. The point I'm trying to make here is that a star's behaviour is dominated by its mass. The mass of star owes to the nature of its birth.

So, how are stars born?

(Image credit: http://www.deepskycolors.com/about.html from APoD.)

Clouds

When a cloud in space has enough material, it may collapse on itself, provided the gas that makes up the cloud is relatively "calm." The end product of such a cloud collapsing on itself is a star, or many stars.I like to explain in very simple terms before progressing on to something more detailed. So...

The forebearer of a star is a cold, dense molecular cloud. Molecules are give-aways for cold and dense clouds, because space is too sparse and thus "hot" to contain many molecules. Provided a molecular cloud is sufficiently dense and quiescent, it will eventually self-gravitate to form an accreting young stellar object (YSO). This means there's a "star-like" object surrounded by a disc of inflowing gas - this is how the star grows. If enough gas has fallen in, the YSO will have begun fusion in its core, and have started its life as a main-sequence star.

At least, this is relatively obvious and well understood in the low mass case of star formation.

Image credit: NASA, Jeff Hester, and Paul Scowen (Arizona State University)

Image credit: NASA, Jeff Hester, and Paul Scowen (Arizona State University)

High mass star formation

The separation from low mass and high mass stars is at 8 solar masses (8 $M_\odot$). The prescription for high mass comes from those stars that end their lives in a supernova, rather than as a planetary nebula.So we would expect that high mass stars are simply low mass stars that have eaten too much - what's special about them?

It turns out that our understanding of a YSO accreting matter is insufficient to explain how high mass stars are truly born. As mentioned previously, if enough gas has fallen in, a YSO will begin fusion. However, as the YSO gains mass, it also shines more light. For the YSO to become "high mass," it must accrete more matter, begins to "blow away" infalling material from shining so brightly. Eventually, the intense brightness of the YSO makes accretion difficult, if not impossible - at least, that's what we understand so far. Research has provided models that allow for stars to grow as big as 20 $M_\odot$, yet we see stars in space greater than 80 $M_\odot$.

Wow, how do these freaks come about? This is the field of research known as high mass star formation (HMSF).

MALT-45

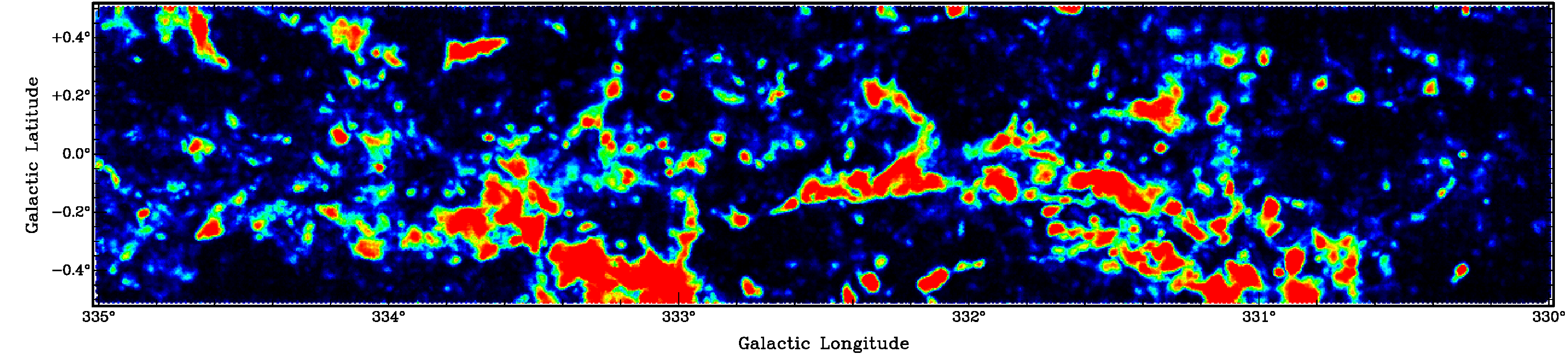

This is where I enter the field of research. One product of my work I am particularly proud of is the above image. This is carbon monosulfide (CS) J=1-0 mapped by MALT-45. Regarding star formation, dense gas highlights where stars are born. The CS we have mapped is particularly useful, as it is only seen in very dense regions. Effectively, we are filtering the Galaxy for really dense clouds, aiding the search and understanding for HMSF.

MALT-45 (Millimetre Astronomers Legacy Team - 45 GHz) is a sensitive, untargeted survey of the Galactic plane for HMSF in the 7mm waveband (which is roughly 45 GHz). “Untargeted” refers to the survey’s mapping technique - a region is selected, and every point in the sky is given equal telescope exposure. This is important to avoid any bias toward known, well studied regions, potentially revealing less obvious cases of HMSF. MALT-45 is conducted upon the Australia Telescope Compact Array (ATCA).

To date, 5 square-degrees have been mapped ($\text{l} = 330 - 335, \text{b} = \pm0.5$), as this amount of data was more than sufficient for the scope of my PhD thesis. My thesis will present data on:

- $\text{CS}$ $(1-0)$

- class I methanol ($\text{CH}_3\text{OH}$) masers at 44 GHz

- $\text{SiO}$ $(1-0)$ $v=1,2,3$ masers

- $\text{SiO}$ $(1-0)$ $v=0$ thermal emission

More detailed information on MALT-45 can be obtained through my publications, particularly the survey results paper (currently in preparation).

Masers

Masers can be thought of as microwave-frequency lasers, occuring naturally in space. Star formation regions and stars themselves can exhibit maser emission in various ways, owing to their energetic properties.

Of particular interest to our research are the class II methanol masers - these have been demonstrated to be associated only with HMSF. MALT-45 extends the methanol maser investigation by searching for the class I cousin. Not every masing molecule has a class “I” and “II,” but methanol is particularly wonderful, as both are associated with star formation. class II emission occurs very near a YSO during accretion, excited by the illumination. class I is collisionally excited, however, and tends to be quite offset from the “site” of star formation. class I masers are an active topic of study, but are still poorly understood.

MALT-45 searches for class I masers in an efficient and sensitive way; all other searches have been targeted towards known regions. Because we are finding new class I masers away from known regions, we may better better understand what they mean. Within the region MALT-45 has mapped for my PhD, approximately 60 new class I methanol masers have been discovered.

Silicon monoxide is another masing molecule that MALT-45 surveys. It is commonly associated with evolved stars, but has been seen in a few star formation regions too. MALT-45 has found around 50 of these in the first survey region.

Technical challenges

MALT-45 is pioneering in a few ways. This project “fills the gap” by undertaking a large-scale mapping of $\text{CS}$, as well as searching for methanol and $\text{SiO}$ masers in an untargeted way. This has not been done before due to an issue of sensitivity. At 7mm wavelengths, a radio telescope’s beam is small (1 minute of arc on the ATCA). Say you want to map a large region of the Galaxy with a small beam; the longer you spend on each point gives you a better sensitivity, but obviously takes longer. Too much time, and the survey is not feasible; too little, and you’re not detecting enough emission. Luckily, MALT-45 has a secret weapon: autocorrelation.

Typically, a radio telescope that is composed of multiple dishes (such as the ATCA) is only used for high-resolution studies. The more dishes you have and the further spread they are, the higher the resolution you obtain. This is called interferometry (or cross-correlation), and is wonderful for many research topics in radio astronomy. However, drawbacks to using many dishes in this way include “resolving-out” extended emission, such as the $\text{CS}$ we are looking for. Usually, to map extended emission, you need to use a single dish telescope.

MALT-45 combines each of the dishes of the ATCA, as if they were all single dishes. This effectively multiplies the collecting area of any single dish, almost like having a very large single dish, and yields a much better sensitivity to emission. Without autocorrelation, achieving a similar sensitivity to what we have already accomplished would be painfully slow.

SHIRTS

MALT-45 is my exclusive PhD project. However, I have been fortunate enough to collaborate with colleague Courtney Brown, nee Jones at UTAS. The SHIRTS project analyses 3-colour images from GLIMPSE for potential $\text{H}\scriptsize\text{II}$ regions, then observes them with the ATCA. Due to the new C/X-band receivers on the ATCA, sensitivity is incredible, and we are able to parameterise the $\text{H}\alpha$ lines associated with the $\text{H}\scriptsize\text{II}$ regions in very short intervals.Once we have observed the $\text{H}\scriptsize\text{II}$ regions, we use the velocity information of each to help describe the structure of our Galaxy. This usually means positioning each $\text{H}\scriptsize\text{II}$ region within a spiral arm of the Milky Way.

(Image credit: Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics, Heidelberg and H.E.S.S.)